Seamanship 401

Finding Refuge

From Hurricanes

& Tropical Storms:

The Finer Points

by David Pascoe

Understanding weather and how to protect your boat from its more violent moments falls under the general heading of seamanship. If you live in a hurricane zone and don't understand these storms, sooner or later you're going to lose your boat.

We all know that from time to time there are what appear to be a lot of false alarms; people say that the media overdoes the news about these storms. Perhaps so, but that's certainly better than underplaying them. Becoming complacent is a fact of life we all have to deal with, or pay the consequences. A false alarm, however, is only a perception because most storms go somewhere and affect someone, but not always you. Thus, a false alarm only pertains to you and where you are in relationship to where the storm goes ashore. Someone's going to get hammered, but it isn't always us.

One of the most important things we need to know about these storms is to (1) to know when it is necessary to prepare so that (2) we avoid needlessly engaging in the huge amount of work involved in preparation, and (3) learn to take the RIGHT action. This essay will discuss how to evaluate your proximity to a storm and how to draw the right conclusions on what to do.

Storm Dynamics

Storm Dynamics are complicated because a hurricane or tropical storm is a spinning vortex that has a direction of movement. Where the storm is going may be very well defined, or, more often, unpredictable. This unfortunate fact means that we usually have little time to prepare when it's suddenly announced that hurricane Bambi is coming our way.

The winds revolve around a center while the storm is moving forward at a certain speed. This causes the wind direction to change as the storm first approaches, and then passes. You already know that if you are directly hit by the eye, you'll experience a complete 360 degree wind shift. But if you're not hit by the eye, the amount of wind shift will be substantially less, usually no more than 90 degrees.

It is this important factor that we should be sure we understand because it is critical to decision making. Direct eye hits are very rare because the storm centers are so small - usually in the range of 10 - 15 miles so that the odds of a direct hit are small. Still, this is not the sort of thing that the average boater can plan for since the science of predicting direct eye-hits is not good. But the odds of being merely close to the center are much higher and thus more predictable, giving us a distinct advantage toward anticipating the proper actions to take.

Coastline Orientation

Which coast you are on plays an important role. In the US we have two major coastline orientations, north-south and east-west. The former is made up of the Atlantic and south Texas seaboards while the later consists only of the northern Gulf coast. The oddball out is the Florida west coast which is largely protected from direct hurricane hits by the peninsula. That is because the predominate hurricane tracks are from the east to southerly directions except for those few storms that seem to have no direction and wander aimlessly around as with TS Amy a few years ago.

The reason that coastline orientation is important has mainly to do with the terminology we use to describe directional relationships of the storm. For example when we are talking about the strong or weak side of a storm. Here we have to talk about whether we're on the east or west, north or south side of the storm.

In order to simplify, I'm going to use the northern Gulf coast as my main example so that I don't have to discuss every coastal orientation at once, which makes for a very messy and hard to read essay. Those of you on a north south coast, please substitute north-south for east-west directional differences. There the strong side is the north side which has the on-shore winds while the south side is weak with offshore winds.

Wind Directions

Of course, few coastlines are highly regular, most being highly irregular, something I'll address further on.

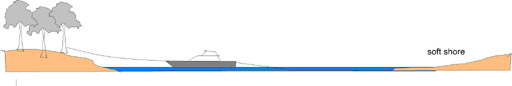

Figure 1 shows a typical north Gulf coast line where we are at Point B, so let's consider how wind direction changes relative to where the storm goes ashore. When storms pass us by to the east (or south) we will be on the weak side where winds will not only be lessened by the storms forward movement, but will also be mainly offshore. Thus, we don't have to worry about storm surge and high water, but usually the opposite. That is the opposite of what we see in the illustration below.

Figure 1. This illustrates the differences in wind direction from the eye wall out to about ten miles as the storm passes due north. If you understand this illustration, you'll have little difficulty predicting wind directions. Keep in mind that the storm is moving, so these wind patterns will change.

It's an entirely different matter when we're on the east or north side, which is the strong side with onshore winds. Here we have hurricane Bambi with a 10 mile diameter eye on a bearing of 325 degrees or NNW. Your boat, located at Point A is another 10 miles outside the eye wall. So far, everything the NHC has predicted has been correct, so you know that about 12 hours in advance that this will be the situation with considerable certainty.

We want to know at this point what directions the winds will be from so we can make a decision as to the exposure of our dock; can we stay or must we leave?

Winds around the eye wall travel in a complete circle around the eye. That's not quite the case outside of the eye wall where the circular diameter is much larger. This causes a change in direction illustrated by Figure. 1 where the wind direction is altered by centrifugal force and are angling inward toward the center. This is important because look what it does to the wind direction there as compared with the eye! If you were on the eastern eye wall you could have a shift of as much as 360 degrees, but outside the eye wall much less. At our position, it's going to be around 90 degrees.

It's a whole lot easier to plan for a 90 degree shift than 360 degrees. With a direct hit, almost no refuge would be safe whereas in our situation many more refuges will be relatively safe due having only a 90 degree wind exposure. It is the fact that the further out from the eye you are, the more stable the wind direction is, that allows us to make sound decisions.

Notice that in Figure 1 the initial winds are from the northeast and at the peak of the storm shift to southeast and when it completely passes the wind then goes to the south, even SSW.

Finding a Hurricane Hole

With these facts in mind, we can look at a chart and begin trying to find a location that will be safe under these circumstances. We will be looking for a windward shore as opposed to a leeward shore. (These terms are confusing because a windward shore is on the leeward side of a land mass whereas a leeward shore is the shore against which the wind is blowing.) What we are seeking, of course, is protection from wind and waves, but we've got another factor to consider which is storm surge. i.e., rising water.

Simply defined, storm surge is the level to which the water will rise resulting from the force of wind, combined with the "humping" up of the sea surface in the eye due to extreme low pressure. This later accounts for surge height is about double within the eye as with immediately outside the eye.

Complicating this issue is the fact that surges along inland waters such as bays will vary from that of oceanic coastlines. Certain types of bays, such as funnel-shaped bays, can actually end up with higher water levels than the immediate coastline.

Funnel shaped bays and inlets (oriented perpendicular to the coastline) are to be particularly avoided (Figure 2), whereas inlets and small bays that are dog-leg shaped afford much better protection. What happens to estuaries and bay that are protected by barrier islands is that the wind, blowing at high speeds over prolonged periods starts to pile water up in these locations. The inability for the water to disperse in bays is the reason why surges can be higher in bays than along coastlines.

For this reason, it's generally best to avoid any location on the leeward side of bays. Choose the windward side of the bay if at all possible and the barrier island is high enough that it won't be over washed by the oceanic surge.

Destin Harbor and most of Santa Rosa Sound are good examples that have barriers that are so low that they will be overwashed and which give a false sense of security to these locations.

The chart in Figure 1 shows four possible refuge sites. Which of the four do you think is the best? The site C would have the least exposure to the winds on this side of the storm while sites A and B have direct exposure with a long fetch in the bay that would be exposed to very large waves. Site D is much too close to the inlet and the ocean.

Figure 2. With a storm

passing to the west (olive green overlay)

This illustration shows which areas of the bay would be relatively safe and those most exposed. North is toward the top.

The West Side

Just because you're on the west side of the storm with offshore winds doesn't automatically imply security. While you have low water to consider and deal with, there is also the matter of exposure to wave action from the opposite direction as in the above example. Here, the safer shore will be on the northern side instead of the south side since the windward/leeward shores have switched due to change in wind direction.

The Eye

This is the one place you hope and pray you never end up for it's really tough for a boat to survive the eye of the storm. However, there were boats that survived the Cat 5, 155 mph winds of Andrew. The key to the survival of those boats was that they were on well protected canals that were oriented mainly perpendicular to the predominant winds. Unless you have access to a far inland canal, survival in the eye is going to be pretty much a matter of luck since otherwise there is little one can do.

Fetch

Protection against wave action involves the issue of fetch, which means the distance over open water which wind blows. The greater the fetch, the higher waves will become. The higher the winds, the less fetch is needed to create equally large waves.

No storm refuge is safe that isn't protected against wave action. One thing that people often overlook is that waves can curl or bend around promontories, as well as bounce off rocks and bulkheads. Figure 3 illustrates just such a situation. This cove has a bulkhead on the leeward side that makes most of the cove unsafe as the waves will bounce off and hit the other side. Conversely, that same cove with a beach on the leeward side would be mostly safe.

Leeward shores on large bays are particularly problematic when it comes to reflected waves and heavy swells bending around promontories, so be wary of such situations.

Figure 3. Waves curve around a promontory and then bounce off a bulkhead rendering the whole marina unsafe.

Timing

The question of seeking safe refuge always involves the critical issue of timing. That's because the exact point of landfall of these storms is harder to predict the further out it is. It is usually not until about 12 hours out that it can be predicted with substantial accuracy. By that time, weather conditions are usually starting to deteriorate. Conversely, if one starts out too soon, a change in direction of the storm is likely to foil all your planning.

Therefore, in doing your planning, it's a good idea to know how long it will take to move your boat to the selected site. Then there's always the problem of the darkness of night. Much of the time we have to prepare is often at night. Thus, good timing gets to be a tricky business. The NHC endeavors to give us 36 hours warning. Unfortunately, the warning area is huge and the accuracy of predicted landfall is minimal this far out.

Even the 24 hour prediction is none too good, but by this time we've got to take action as this will give us a full day of daylight, less of which is just not adequate.

Choosing a Primary Site

It's hard enough for most of us to locate a good site without all these other factors to consider, but the time it takes to get the boat to the site is a major factor. Naturally, we want to find something as close as possible and be sure we know exactly how long it takes to get there because we'll need to a lot several hours to making preparations after arrival, particularly when anchoring as that can be time consuming.

A Dinghy Helps

Having a dinghy adds an extra dimension to what we can or cannot do. As noted earlier and in other articles, docks can be a boat's worst enemy. So can anchoring in bad holding ground, so a good compromise is a little of both. Having a dinghy allows one to do tie-offs and setting of anchors that would not otherwise be possible.

Consider the options of tying off the bow to a shore side tree or piling and setting anchors off the stern. I've seen many enterprising boaters use many different combinations of these very successfully. Tying off a good, protected windward shore solves all the problems of storm surge and docks as extra long lines will allow the boat to rise to any surge height the storm can throw at you. It also eliminates the risk of getting smashed up by other other boats, which is a major risk in most situations and a major reason why you want to seek shelter elsewhere. Unless you want to swim, only a dinghy will allow you to do this.

Figure 4. Mooring off the shoreline of a protected refuge with a soft shore to leeward. Trees provide extra wind protection. Forested shorelines can knock wind speed down by as much as 60% several hundred yards out.

Risks of Going Ashore

It may seem hard to believe, but boats that wash ashore generally suffer a lot less damage than those that get battered to pieces tied to docks in marinas when they go into marshy or sandy beach heads. Choosing an anchorage in an estuary or small bay with soft shorelines (sand or reeds) is a good option as the boat will sustain little damage in these situations. Yep, there will be a pretty hefty salvage charge to get her back afloat, plus prop and rudder damage, but that is a small price to pay compared to the blender-like actions of crowded marinas, getting skewered on pilings or going against hard bulkheads.

If you're faced with a direct eye strike, anchoring out in any reasonable refuge with the idea of the boat being blown ashore for a soft landing is a good strategy for defeating total destruction.

It would take an entire book to explore all the possibilities and discuss all the details, but hopefully this short article will give you some idea of how to begin your planning.

Notice

The above information is based upon the author's personal , but informal, studies of hurricanes and their effects over 30 years and evaluation of at least a dozen hurricanes and even more tropical storms. The author is not a degreed research scientist. This information and experience has been made available simply because there is no official agency that has done so. Beware that the author's experience and conclusions drawn from it may contain errors. No assertion is hereby made that this information is absolutely correct; it is the author's opinion.

Posted September 29, 2002

Visit davidpascoe.com for his power boat books

Visit davidpascoe.com for his power boat books David Pascoe - Biography

David Pascoe is a second generation marine surveyor in his family who began his surveying career at age 16 as an apprentice in 1965 as the era of wooden boats was drawing to a close.

Certified by the National Association of Marine Surveyors in 1972, he has conducted over 5,000 pre purchase surveys in addition to having conducted hundreds of boating accident investigations, including fires, sinkings, hull failures and machinery failure analysis.

Over forty years of knowledge and experience are brought to bear in following books. David Pascoe is the author of:

In addition to readers in the United States, boaters and boat industry professionals worldwide from nearly 80 countries have purchased David Pascoe's books, since introduction of his first book in 2001.

In 2012, David Pascoe has retired from marine surveying business at age 65.

On November 23rd, 2018, David Pascoe has passed away at age 71.

Biography - Long version